(1) Learning Outcomes

After working through this module you will be able to:- Describe the core features of tradeable agricultural commodities.

- Explain to someone that a futures contract is equivalent to a standardized forward contract, in which case there is only a future commitment to buy or sell

- Explain the price discovery and risk transfer roles of a futures market.

- Identify the role of long and short positions, and contract offsetting.

- Show how arbitrage ensures spot and futures price convergence.

- Calculate gains and losses on a futures transaction.

- Explain the role of initial and maintenance margins.

- Mark-to-market futures transactions and calculate volume and open interest

(2) Recommended Videos Readings

There has been a lot written about commodity futures. Most of what you will find online has been written from the perspective of an investor or a trading professional with a background in finance. It is hard to find good reading material which emphasizes the economics of commodity futures and which focues exclusively on agricultural commodities. In addition, the videos and readings will mention things that have been "swept under the rug" in this module in order to keep the discussion focused. For example, this module emphasizes that if a futures contract is not offset then physical delivery of the commodity is required (i.e., literally take your truck to a warehouse in Chicago to make or accept delivery). In reality, an increasing number of commodity futures are cash settled, which means that settlement requires sending to (or receiving from) the CME the difference between the spot price and futures price rather than physically delivering the commodity (Investopedia). The concept of cash settlement is not mentioned in this module.

The bottom line is that you will find a significant difference between the content of the recommended readings and the content of this module. You should still spend some time with the the videos and readings listed below but when doing so keep in mind that you will be tested only on the content of this module.

CME Educational Videos and the accompanying narrative provide a great overview of commodity futures. There is no need to register for the free CME course but if you like to track your progress then you should register. The four most important videos are linked below.

- Definition of a Futures Contract

- Get to Know Futures Expiration and Settlement

- Calculating Futures Contract Profit and Loss

- Futures Contracts Compared to Forwards

(3) Global Trade in Commodities

Commodities which trade on futures markets consist of energy (e.g., oil, natural gas, propane, ethanol), precious metals (e.g., gold, platinum, silver), industrials (e.g., copper, tin, aluminum), forestry (e.g., softwood lumber) and softs (e.g., coffee, cocoa, sugar, orange juice, livestock and agriculture). The livestock subset consists of hogs and cattle, and the agriculture subset consists of the major crops, which includes corn/maize, wheat, soybeans, canola/rapeseed, crude palm oil and rice. The agriculture subset also includes semi-processed commodities such as soybean meal and soybean oil. In this class we mainly focus on the agricultural commodities which trade on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME)

Commodity futures was historically dominated by trade in agricultural commodities but in today's commodity market energy commodities are dominant. The five top traded commodities on the CME according to August 26, 2021 trading volume includes crude oil (698,386), natural gas (652,825), corn (202,984), soybeans (123,945) and SRW wheat (91,982). The livestock commodities have much lower trading volumes: hogs (27,051) and feeder cattle (12,733). A corn contract consists of 5000 bushels and the current price of corn is about $5.50/bu. This means that on August 26 the total traded value of CME corn futures was about US$5.6 billion. Compare this to the annual value of U.S. corn production, which was about US$61 billion in 2020.

Agricultural commodities such as corn, soybeans and wheat are very important in food, livestock and biofuel supply chains. For example, the Wikipedia entry for "Corn Production in the United States" shows that in 2019 about 33% of U.S. corn was used for livestock feed, 27% for ethanol, 11 percent for export and 11 percent for other processing, which includes the production of high fructose corn syrup, starch and cereals. High fructose corn syrup is a sweetener which is widely used in beverages and baked goods. The August, 2021 USDA World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE) report indicates that about 4.3 billion bushels of soybeans are expected to be produced in the U.S. in 2021, and of this amount about 2.2 billion bushels will be crushed domestically, and 2.0 billion bushels will be exported. Crushed soybeans consists of soybean meal, which is primarily used for livestock feed, and soybean oil, which is used for food, industrial applications and biodiesel. According to the National Association of Wheat Growers, about half of U.S. produced wheat is exporter and the other half is used domestically for processing into flour, noodles, and breakfast cereal. Low quality wheat is used as a livestock feed.

Agricultural commodities trade globally, mainly by large multinational firms such as the ABC's: Archer Daniels Midland, Bunge and Cargill. Other large companies include Louis Dreyfs and various grain cooperatives. These companies operate a network of country elevators in the grain growing regions, terminal elevators in the export locations and processing facilties. A typical export transaction involves the company purchasing the grain from the farmer either directly or on contract, using rail and barge to move the grain to export position and then using ocean freighters to ship the grain to overseas customers. Most of the freighters that you see anchored off the beaches of Vancouver are grain freighters waiting to be filled from the assortment of terminal elevators in Vancouver

Multinational grain companies often bid in an import tender, which is sponsored by a state-owned enterprise. For example, the U.S. multinational, Cargill, may source wheat in Romania and bid to sell that wheat to GASC, which is the Egyptian state-owned importer of wheat. Consider the following July 5, 2021 report from Market Watch :

Romanian wheat was the cheapest on offer at an Egyptian international wheat tender Monday, according to a lineup of offers seen by The Wall Street Journal.

The cheapest bid out of a total of 18 bids was $237.94 a metric ton for a 60,000-ton cargo of Romanian wheat.

Egypt's state import agency--the General Authority for Supply Commodities--launched the tender Saturday, saying it was seeking an unspecified amount of wheat for shipment between Sept. 1 and Sept. 15.

GASC received eight bids of Romanian wheat, five of Russian wheat, and five of Ukrainian wheat.

Romanian offers ranged in price from $237.94 to $243.50 a ton. Ukrainian bids ranged in price from $239.45 to $246 a ton. Russian bids ranged from $238.10 to $245 a ton.

Egypt is the world's largest wheat importer and market participants view the country's tenders as a guide to setting benchmark prices.

At an international wheat tender last month, GASC bought 180,000 tons of Romanian wheat for $242.93 a metric ton plus freight costs of $27.85 a ton.

(4) What is a Commodity Futures Market?

A storable commodity such as soybeans or sugar have spot prices and forward prices. A spot price is equivalent to an immediate-sale cash price. Spot prices are location specific with lower prices being observed in commodity surplus regions and higher prices being observed in commodity deficit regions. A forward price is the price associated with future sale/delivery of the commodity. A forward price is typically associated with a forward contract, such as a deferred delivery contract which specifies the (forward) price the farmer will be paid by a soybean crusher when the soybeans are delivered in two months' time. In a risk neutral environment, economic theory tells us that a contract's forward price is an estimate of the local cash price which is expected to prevail at the time the commodity is delivered.

In contrast to a forward contract, a futures contract is highly standardized and trade only in centralized exchanges. Each futures contract has a designated expiry date, which is equivalent to the delivery date of a forward contract. For example, in August of 2021 there were 15 Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) soft red winter (SRW) wheat contracts that were actively trading. The expiry/delivery dates are Sep 2021, Dec 2021, Mar 2022, May 2022, July 2022, Sep 2022 etc. until Jul 2024.

There are only a small number of futures exchanges which trade futures for agricultural commodities. For example, soybeans trade in the U.S. Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) and the Chinese Dalian Commodity Exchange (DCE). The Intercontinental Exchange (ICE) established soybean trading in 2012 but abandoned soybean, corn and wheat contracts in 2018 due to low liquidity (Financial Times) . Soybeans trade in a global market and so if there did exist multiple exchanges outside of China they would track a similar global price of soybeans. Traders are attracted to the most liquid market, and in this case it is the long-established CME market.

Futures markets exist for price risk transfer and for price discovery. It would be highly inefficient for traders to independently discover prices at individual spot market locations (e.g., a soybean export location in Brazil, a soybean import location in Rotterdam and a soybean crushing location in the U.S. Midwest). A futures price allows for efficient price discovery in a single centralized market such as the CME. The various spot prices are locally discovered based on the centrally-discovered futures price and accounting for local supply and demand conditions. Price discovery is efficient in a futures market because a large number of traders with detailed knowledge of macro economic variables, commodity stock piles, global weather reports, etc can enter the market at comparatively low cost. Futures contracts were historically determined in "open outcry" trading pits but now most contracts are priced electronically.

Futures contracts also allow for the efficient transfer of price risk. For example, a mid-sized agricultural cooperative in the U.S. Midwest will offer local farmers deferred delivery contracts. By guaranteeing a buy price at a future point in time, the cooperative is now exposed to price risk. The cooperative will typically use a futures contract to hedge and thus significantly reduce this price risk. The economics of hedging is examined in detail later in this course.

If you trade commodity futures you must decide if you will take a long or short position. Although long is equivalent to "buy" and short is equivalent to "sell", you are not actually buying or selling anything when you enter the contract. This is different than when buy or sell a stock such Rogers or Bombardier on the Toronto Stock Exchange (TSE).

Short Position: A commitment to deliver (sell) at a pre-specified future date and price.

Long Position: A commitment to accept delivery (buy) at a pre-specified future date and price.

The next section provides a more detailed comparison of a forward and futures contract.

(5) Forward Pricing Concept

Futures vs. Forward Contract

Investopedia defines a forward contract as:

"A customized contract between two parties to buy or sell a (commodity) at a specified price on a future date."

Forward contracts are typically held by the original buyer and seller until the transaction is completed (i.e., the seller delivers the commodity to the buyer and then is paid the previously agreed-upon price). The deferred delivery contract with a locked-in price is the most common forward contract in agriculture but there are several variations (e.g., see alternative contracts offered by Archers Daniel Midland (ADM) , which is a major grain buyer in western Canada.

It is worth emphasizing that a futures contract is equivalent to a standardized forward contract. Farmers and grain companies do not buy and sell forward contracts, and similarly traders and investors do not buy and sell futures contracts. Confusion sets in because traders must commit cash to trade futures whereas there is no up-front cash transaction with a forward contract. The up-front cash commitment that is associated with a futures contract is equivalent to a security deposit when you rent an apartment -- more on this below.

Students often forget that unlike stocks, futures contracts are not purchased and sold. One reason for this misconception is that traders often talk about "buying" futures, when they really mean taking a long position, and "selling" futures, when they really mean taking a short position. Short selling in the stock market is generally complicated because it involves borrowing the stock, selling it and eventually rebuying the stock to repay the loan. In contrast, short "selling" in the futures market is just as easy as long "buying".

There are four important differences between a commodity futures contract and a forward contract:

- Futures contracts trade in centralized exchanges rather than being negotiated by two parties in a decentralized location;

- Futures contracts are standardized (e.g., the same delivery date, location, quality and quantity for all traders of a particular contract) rather than being individually customized;

- Each contract has a trader on the long side of the transaction and another trader on the short side but the exchange clearing house serves as an intermediary ==> trading is anonymous; and

- Contracts are typically offset prior to the contract's expiry/delivery date, which means that when the delivery date arrives there is no physical delivery of the commodity.

Each of these four differences are discussed in turn.

Centralized Exchanges

Wikipedia shows the centralized futures exchanges for agricultural commodities. The four platforms are: (1) The Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME), which includes the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT); (2) the Dalian Commodity Exchange in China; (3) the Intercontinental Exchange (ICE), which operates a consortium of exchanges, including the Winnipeg Commodity Exchange in Canada; and (4) the Euronext in the EU.

Standardized Contracts

CME futures contracts for the major grains such as corn, soybeans and wheat trade in 5000 bushel units. This means that if you go long one CME wheat contract and fail to offset your contract by the delivery date, you are obligated to accept delivery of 5000 bushels of wheat. These CME grains contracts are priced in cents per bushel. EU corn contracts which trade on the Euronext exchange trade in 50 metric tonne units, and are priced in euros per metric tonne. There are 36.74 bushels per tonne for wheat and soybeans, and 39.37 bushels per tonne for corn. CME publishes a calendar which shows the precise expiry/delivery date of each contract.

When viewing the CME calendar for corn notice the codes for each contract. The first five contracts have codes CU21, CZ21, CH22, CK22 and CN22. The "C" stands for corn, the second letter stands for the expiry month (U for September, Z for December, H for March, K for May and N for July) and the last pair of digits stand for the expiry year. These codes are particularly important when working with data purchased from the CME.

You may be wondering how product quality is standardized. Typically the futures contract is specified for a #2 grade of the product. A premium is specified if a higher grade is delivered, and a discount is specified if a lower grade is delivered. Similarly, the delivery location for the major CME grains contracts is Chicago. However, a schedule is posted which identifies price discounts and premiums if the commodity is delivered to an authorized location outside of Chicago.

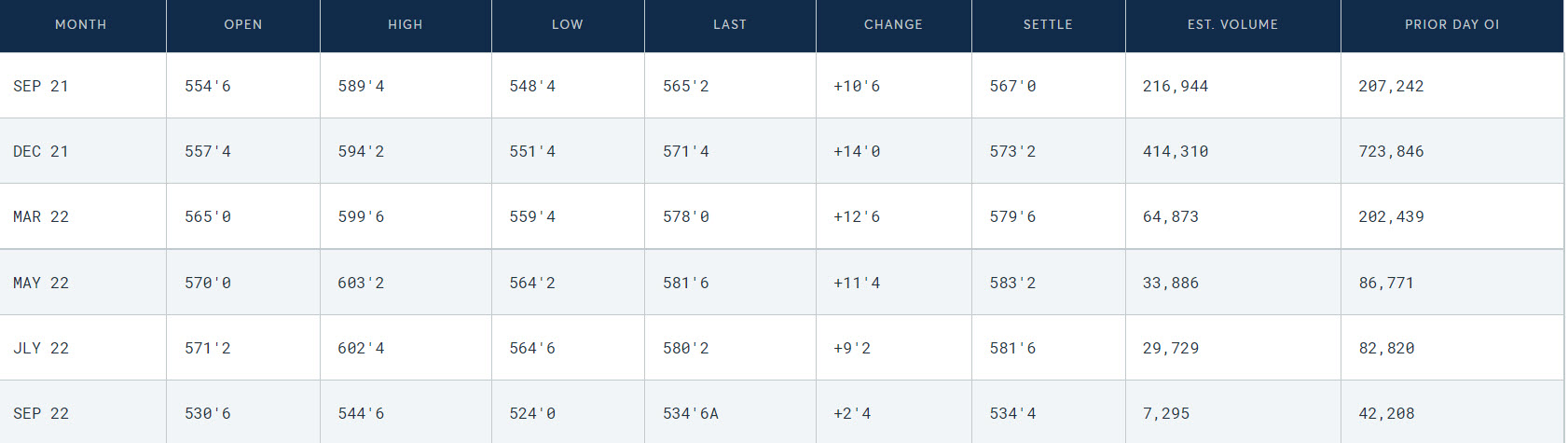

You may also be wondering how to read the price information for CME-traded commodities. For example, CME Corn may be shown as trading at 554'6. The "554" refers to 554 cents per bushel, and the " '6 " refers to 6/8 (or 3/4 of a cent). Thus, 554'6 is equivalent to $5.5475 dollars per bushel.

(6) Important Characteristics of Commodity Futures

Clearing House and Order Book

An important drawback of a decentralized forward contract is counterparty risk. Because the price will increase or decrease after the forward contract is signed the buyer or the seller will have an incentive to not honour the contract. The only recourse for non-comliance is a law suit. This type of counterparty risk is not present in a futures market because the clearing house serves as an intermediary for all trades.

As its name suggests, after trading is complete each day the clearing house calculates profits and losses and updates the traders' margin accounts. By requiring traders to maintain a margin balance and forcing a trader out of the market if his or her margin balance falls below a threshold level, the clearing house ensures that all financial commitments are honoured by all traders.

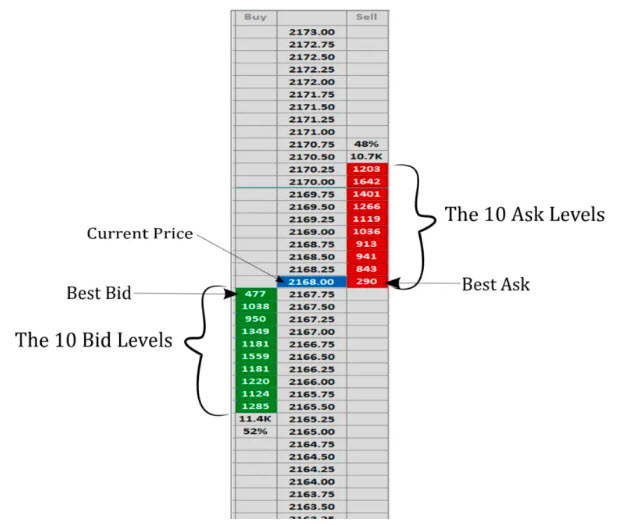

The order book is central to electronic trading. Most traders submit limit orders rather than market orders. Traders who wish to take a long futures position submit a bid, and traders who wish to take a short futures position submit an ask. With a limit order, long traders are willing to enter the market at any price equal to or below the ask, and short traders are willing to enter the market at any price equal to or above the ask. A trade is executed if there exists matching bids and asks.

In the figure below the price in the middle column is descending. The green shaded section of the left column shows the number of traders whose bid price matches the corresponding price in the middle columns. The red shaded section of the right column shows the number of traders whose ask price matches the corresponding price in the middle column. In this example, the market price is 2168 and if there is no more change the bids below 2168 and the asks above 2168 will go unfilled. It should be noted that day traders can purchase a subscription to the order book and use the data within to construct trading strategies.

It is important to keep in mind that each futures market transaction requires one trader on the long side and one trader on the sell side. However, unlike a forward contract, the instant the trade is executed the pair of traders who are on either side of the contract have no more connection. The single contract is converted into two contracts. Specifically, the clearing house pairs with the long trader by providing a short position at the transaction price. Similarly, the clearing house pairs with the short trader by providing a long position at the transaction price. The contracts are zero sum, which means that the clearing house does not earn or lose money as the market price changes. Indeed, every dollar the clearing house gains or losses when matched with the long trader is exactly offset by the loss or gain when matched with the short trader. If the long trader earns $400 in profit due to a favourable price change then it must be the case that the short trader lost $400 because the price change was unfavourable.

Contract Offsetting

A trader with a long (short) position has the obligation to accept delivery (make delivery) of the commodity at a predetermined date and location. For CME grains, trading of a particular contract terminates, which means that delivery must take place if the contract has not yet been offset, on the business day prior to the 15th day of the contract month. Most traders (perhaps 95 percent for most commodities) do not wish to handle the physical commodity and as such they choose to offset their position prior to the expiry of the futures contract.

A trader with a long (short) position in December, 2021 corn can offset by taking a long (short) position in December, 2021 corn. The clearing house updates the traders account by comparing the price difference for the two trades. For example, if a trader took a long December, 2021 corn position when the price was $5.75/bu and subsequently offset by taking a short December, 2021 corn position when the price was $5.90/bu, the clearing house would credit the trader with a $0.15/bu gain. This is because the short is equivalent to selling at $5.90 and the long is equivalent to buying at $5.75.

Volume and Open Interest

The figure below shows a price chart for CME corn on August 12, 2021. The opening and settle/closing prices are reported for the various trading months. The reason for the price differnces for the different contracts will be examined in detail later in this module. The last two columns show the the trading volume and prior-day open interest. These two variables define daily activity and cumulative activity, respectively.

Volume: The number of futures trades executed for a particular day. Each trade requires one long and one short position.

Open Interest: The number of open contracts as measured by the number of long contracts or or the number of short contracts that have not yet been settled (either offset or delivery option chosen).

The main difference between open interest and volume is that volume measures the activities of new trades whereas open interest is a measure of the cumulative net position of all traders from the day the contract began to trade. Volume is typically largest for the nearby futures contract, although it usually drops off rapidly in the last few days prior to the contract expiring. Open interest typically grows steadily, starting about when the contract is within a year of expiry. When the contact nears the last month of trading prior to expiry open interest typically falls off rapidly as traders offset their positions and take new positions with contracts that have a longer maturity.

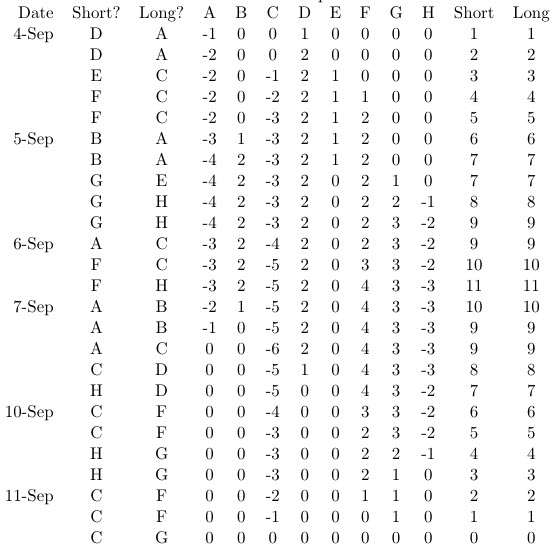

The table below shows an example of how open interest and volume are calculated. A positive value indicates a long position and a negative value indicates a short position. The first two columns identifies which pair of traders took the long and short positions. The middle columns are a running total of the net position of each trader. The last two columns show the total number of long and short positions. Mostly importantly, the bottom row of each day shows the outstanding long and short positions for each trader at the end of the day. For example, at the end of the first day there are five outstanding short and five outstanding long contracts. By the end of the second day these values have risen to nine. Open interest is therefore 5 for the first day, 9 for the second day, 11 for the third day, etc. Notice that open interest begins to decline toward zero as the various traders offset their positions and exit out of the market. Volume is simply the number of rows for each day. Thus volume is five for the first day, five for the second day, three for the third day, etc.

Margin and Marking to Market

Traders of commodity futures must maintain a balance in their margin accounts. This balance is large enough to ensure that if the commodity's price moves against the trader, the loss on the trade can be covered by using the funds in the trader's margin account. It is important to distinguish between the two alternative types of margins:

Initial Margin: The minimum margin account balance when the trader takes a position in a new contract (e.g., $1000 for a 5000 bushel CME corn contract).

Maintenance Margin: The minimum amount that must be maintained in the margin account while trading is on going (e.g., $700 for a 5000 bushel CME contract).

If a trader's balance falls below the maintenance margin then the trader will receive a margin call. If this happens the trader must immediately deposit more money into her margin account. If she fails to do this then her position will be automatically liquidated.

Marking to market means that after each trading session the margin account of each trader is updated with the profits or losses that were incurred for the current trading session. In the previous example, it was shown that when the trader offset her position in the corn market, the clearing house added the $0.15/bu to the trader's margin account. Marking to market means that daily profits and losses are calculated as if the trade was offset at the market's closing price. Marking to market ensures that the trader's margin account balance less the initial margin and margin contributions or withdrawals reflects the cumulative gain or loss in profits on the contract.

Suppose on September 15 Sally takes a long position in the wheat market at $8.00/bu. The wheat market closes on September 15 at $7.90/bu. Marketing to market is equivalent to offsetting Sally's long position with a short contract at price $7.90 and then bringing Sally back into the market with a new long contract at price $7.90/bu. Sally loses $0.10/bu on a 5000 bushel contract and so her margin account balance is reduced by $500. Suppose on September 16 Sally maintains her long position and makes no new trades. Also suppose the market price increases to $7.95. At the end of the day, marking to market is equivalent to offsetting Sally's long position at price $7.95/bu. Her contract had been marked to $7.90 at the beginning of the day, and so Sally earns $0.05/bu on the transaction. Thus, $250 will be deposited to Sally's margin account. On September 17 Sally offsets her long position at price $8.08/bu. She began the day with her long contract marked to $7.95/bu, and so Sally gains $0.13/bu. The clearing house therefore deposits $650 to her margin account. Her cumulative gain is -500 + 250 + 650 = $400. This gain is the same as if we calculated her profits as (-7.50 + 8.08)*5000.

Margin and Trading Leverage

Trading commodity futures is highly risky and it is for this reason that individual investors are generally not able to trade futures directly. Trading futures is much riskier than trading stocks because of the leverage associated with trading on a margin. For example, with a 10 percent initial margin requirement, and $6.00/bu futures price for corn, a trader is required to deposit 0.1*6.00*5000 = $3000 to trade one CME corn contract. If the futures price changes by say 5 percent, the gain or loss is $0.30/bu, or 0.30*5000 = $1500. Relative to the initial margin deposit of $3000, this represents a 50 percent plus or minus return. In contrast, if the investor spent $3000 to purchase Google stock and the stock price changed by 5 percent, then the investors return is plus or minus 5 percent. The leverage implied by trading on a margin rather than the full value of the commodity makes trading futures very high risk!

Futures and Spot Price Convergence

Even though most traders offset their futures contracts prior to contract expiry, the option to make or accept delivery is very important. Indeed, the delivery option ensures that the spot price and the futures price of the commodity converge when the contract expires (this assumes the commodity is located in Chicago, which is the delivery location for the futures contract). Suppose the futures price was above the spot price and the futures contract was about to expire. With zero price risk a trader could purchase the commodity in the spot market, and at the same time take a short futures position. When the contract expires the next day, the trader would delivery the commodity to satisfy the requirements of the short contract, and in doing so would receive the higher price, thus earning a profit. In the opposite case where the futures price was less than the spot price, the trader would take a long position, accept delivery of the commodity and then immediately sell the commodity on the spot market for a profit. We will examine the convergence of the spot and futures price in greater detail later in the semester.